Introduction

InPlanet achieved the next historic milestone in the Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) landscape with its second issuance (and only fourth ever globally) of certified Enhanced Rock Weathering (ERW) carbon credits from Project Aracari. A total of 319.97 tCDR were verified for this project via the deployment of basalt on citrus orchards. The carbon credits were the 2nd issued under the Isometric enhanced weathering protocol, following InPlanet’s issuance of the world’s first ERW carbon credits at the end of last year. They were independently verified by 350 solutions. From this project, 200 tonnes have been delivered to our partner, Klimate.

Beyond the durable carbon removal achieved through this project, the agronomic co-benefits of deploying basalt rock powder were also studied, which are shared in this blog post.

Brazil is the world’s leading producer of oranges (USDA, 2025), supplying a significant share of the global juice market. Citrus trees are nutrient-demanding and highly sensitive to biotic and abiotic stresses, including bacterial infections such as greening and prolonged drought. These are conditions under which basalt rock powder, with its potential to release nutrients and ameliorate soil pH (Swoboda et al. 2022), may provide benefit. Additionally, basalt application may improve water availability through improving soil physical properties (Costanzo et al. 2025).

Project Background

Project Aracari involves two commercial orange farms located in central São Paulo state. Together, they cover 358 hectares, of which 339 hectares received a basalt rock powder application, while 19 hectares served as untreated controls.

Basalt spreading occurred between August and November 2024 at an application rate of 20 tonnes per hectare in the deployment areas.

The farms differ in their soil types and fertilization practices:

Farm 1 – business as usual consists mainly of the Argissolo Vermelho soil type, with some areas of Latossolo Vermelho. All areas received limestone (at a variable rate up to 7 t/ha) and NPK fertilization, in accordance with normal agricultural practice.

Farm 2 – limestone and gypsum substitution is dominated by the soil type Latossolo Vermelho. All farm plots received NK fertilization and P-fertilizer. In this farm, limestone (2.8 t/ha) and gypsum (1.2 t/ha) was directly substituted with 20 tonnes/ha of basalt in the deployment area, while the control area still received limestone and gypsum application.

Soil type note: Latossolos are deeply weathered, well-drained, and rich in iron oxides, whereas Argissolos show textural differentiation and thus stronger differences in nutrient retention and acidity between surface and subsurface.

Analysis

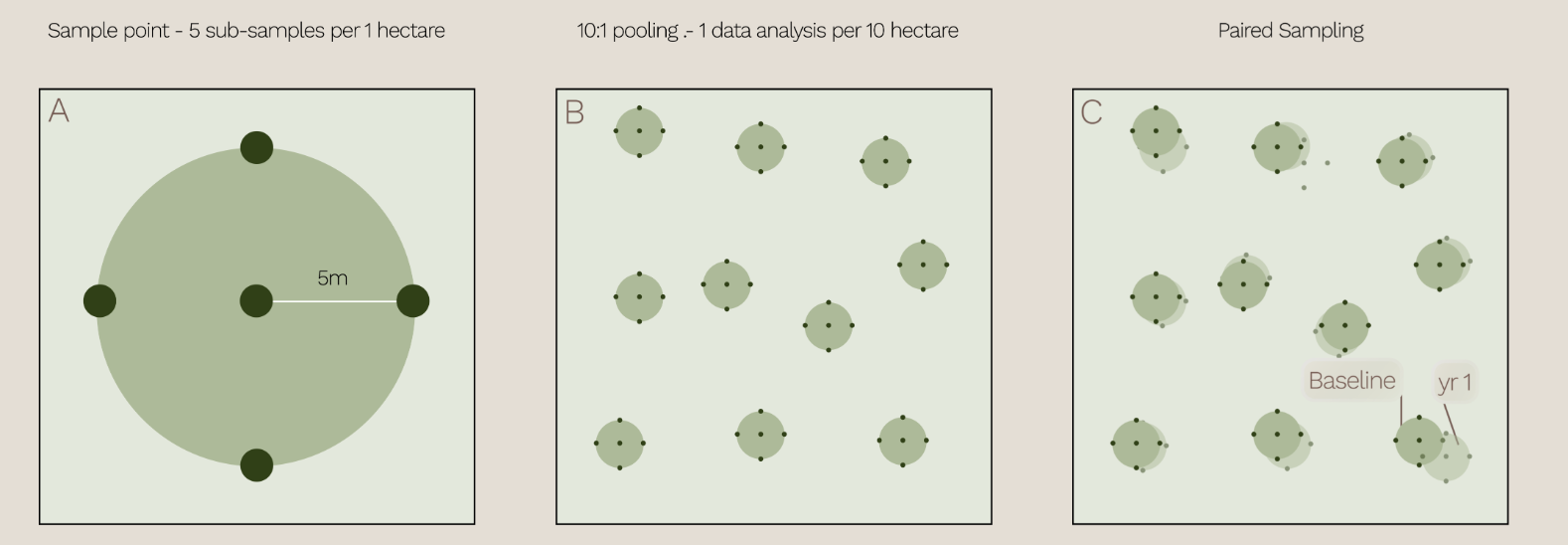

Soil samples have been collected (0-20cm) at baseline before the rock powder spreading and 9 months later using GIS-assisted paired sampling (i.e., samples were collected at the same geographical locations as the baseline sampling). This method allows direct evaluation of chemical and agronomical changes (Δ) at individual sampling points, greatly reducing the noise introduced by heterogeneous field conditions.

In addition, biometric data from experimental plots were collected to assess tree growth. Yield and fruit quality analyses are still ongoing, as the harvest has not been fully completed.

Agronomic Field Results

Effects on organic matter and soil pH

Organic matter and soil pH are major soil health metrics crucial for the availability of nutrients and plant available water, and ultimately higher yield stability (Lal, 2020).

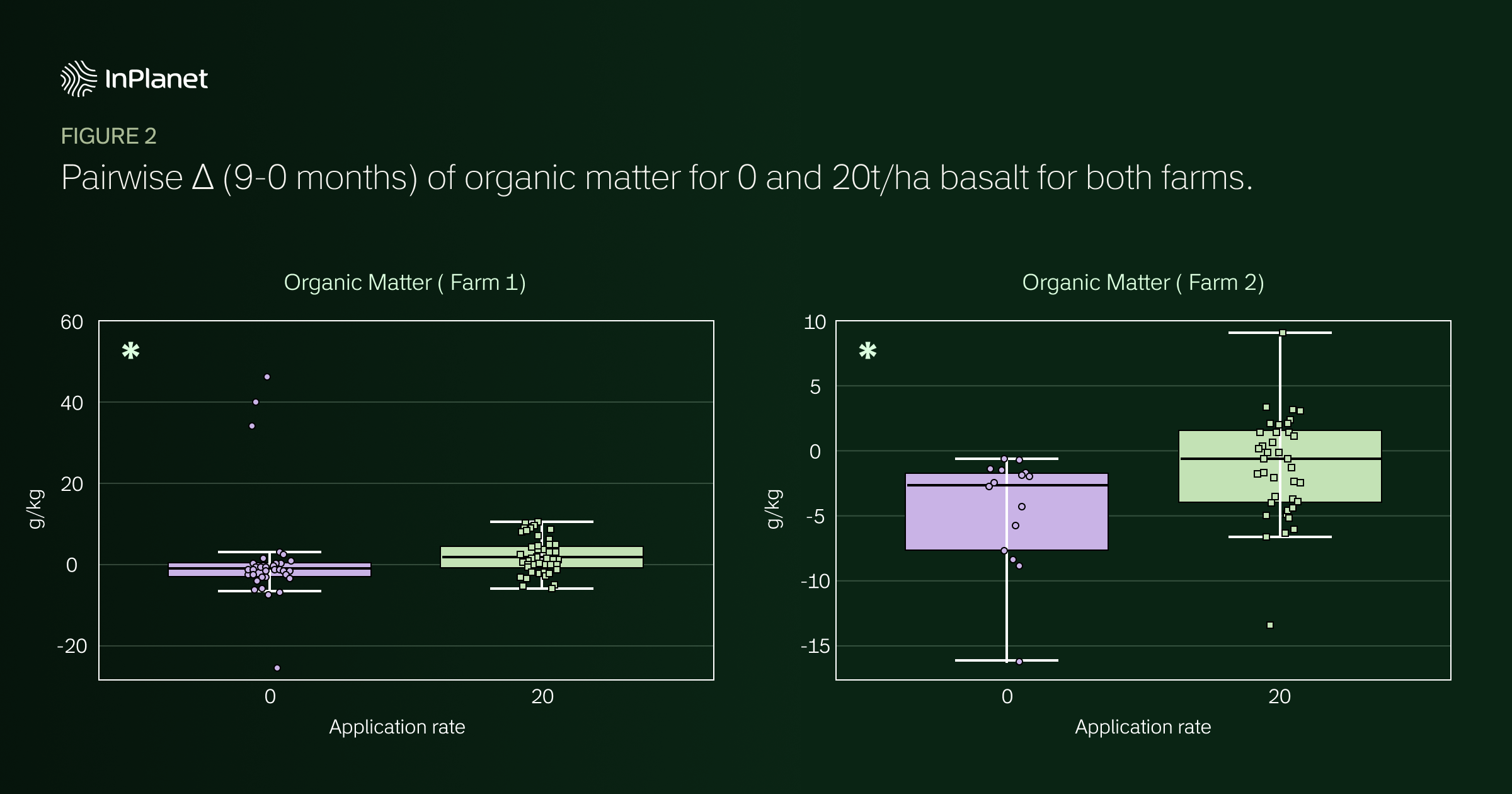

On both farms, a statistically significant improvement (Wilcoxon rank-sum test) in the difference (Δ) in soil organic matter from baseline to post-application was seen relative to the control (Figure 2). The difference for each paired sample point is calculated by the post-weathering value minus the baseline. A positive value for the pairwise Δ graphs thus indicates an increase of the respective soil metric, and a negative value a decline. The absolute values for pH and organic matter after 9 months are documented in Table 1.

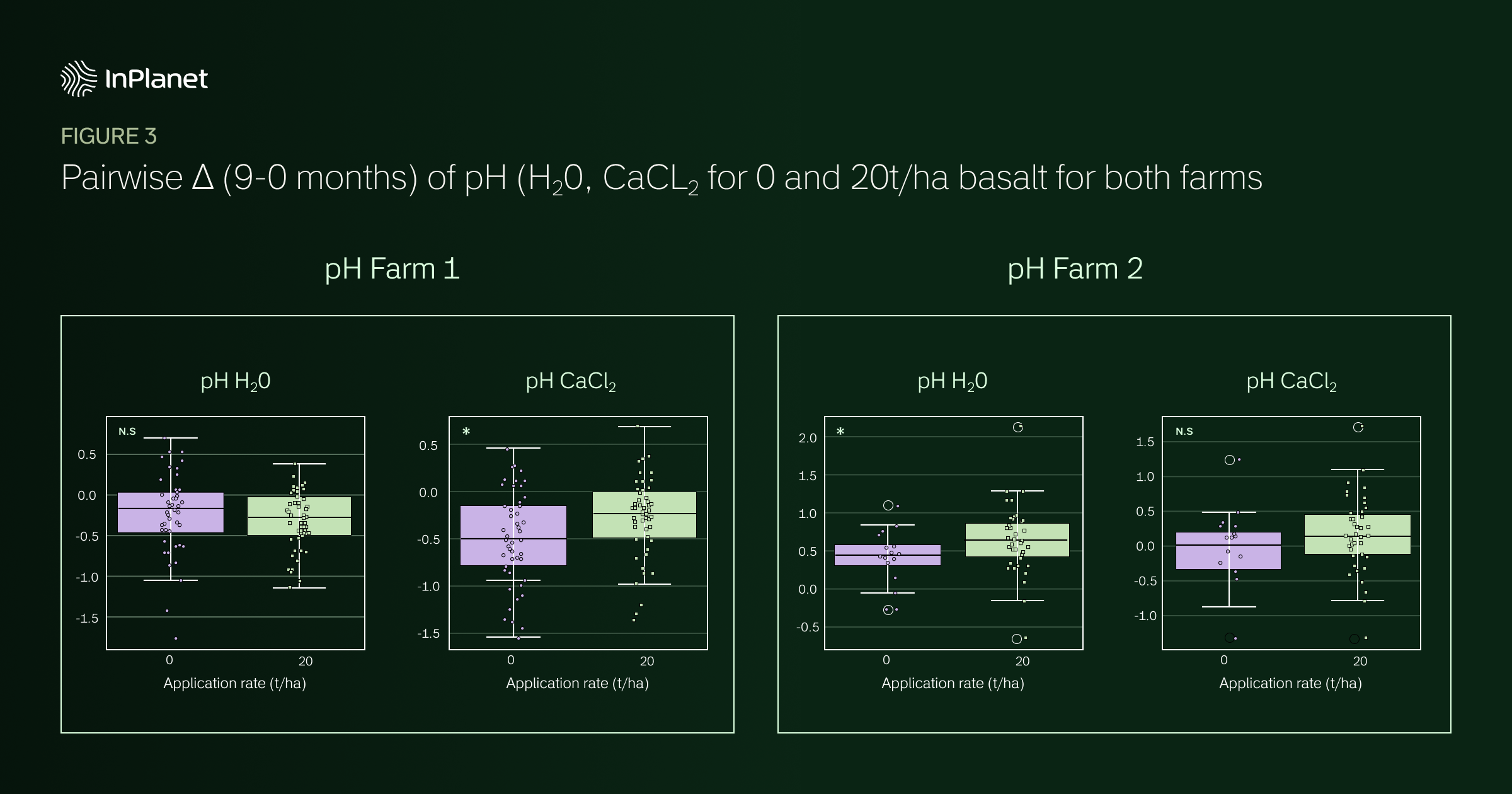

On farm 1, the Δ soil pHH2O slightly decreased (statistically not significant, details in Table 1) for the basalt application relative to the control, whereas the Δ soil pHCaCl2 increased (statistically significant) for basalt (Figure 3). The differences between pHH2O and pHCaCl2 are described in the pH note below.

On farm 2, basalt application improved both the Δ soil pHH2O (statistically significant) and pHCaCl2 (statistically not significant) compared to the control. Importantly, in Farm 2, limestone was only applied in the control area and fully replaced in the basalt deployment area. This indicates that basalt can substitute limestone as a pH corrective (Fig. 3).

Soil pH note: the pHH2O is measured in water and reflects the active acidity (H+ already in the soil solution). The pHH2O is the basis for most soil science concepts. The pHCaCl2 is measured in a 0.01 M CaCl₂ solution that is intended to represent the ionic strength of the soil solution. The more controlled ionic strength of pHCaCl2 is thus often more reproducible as it is less affected by soil physical and chemical fluctuations, and is closer to the soil´s potential acidity (H⁺ + Al³⁺ on the exchange sites). However, the pHCaCl2 requires careful conversion to compare with the benchmark pHH2O (Sanchez, 2019)

Furthermore, the pairwise comparison on farm 2 showed that basalt performed better in improving the baseline pH compared to the control with limestone, although the absolute values for pH after 9 months were actually higher in the control areas. The reason for this is that control areas had a substantially higher (0.485 units) baseline pH than the basalt deployment areas.

Nutrient Availability

Farm 1 – “Business as usual”

On Farm 1, fertilisers were applied in a “business as usual scenario”, meaning that both the basalt amended deployment areas and the control areas had NPK fertilizers applied.

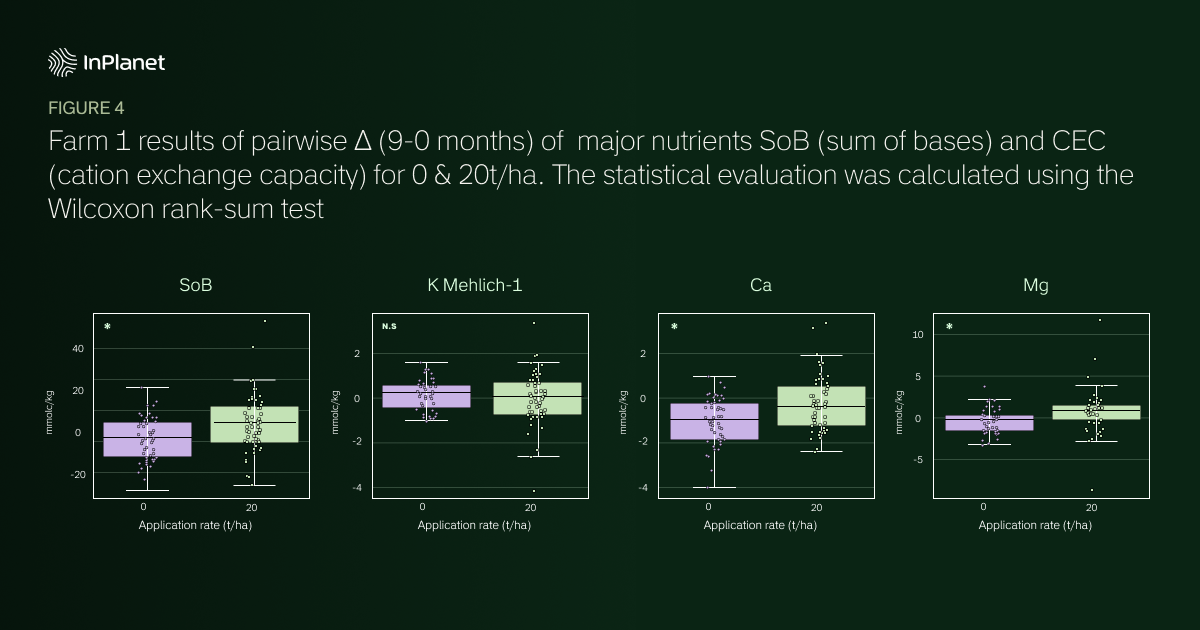

Over the course of 9 months, and apart from potassium (K), the difference (Δ) between post-weathering and baseline improved for all soil nutrients in response to basalt application compared to the control (Figure 4). Statistically significant improvements were found for exchangeable Ca and Mg (details of the nutrient extractions are provided in the Nutrient analysis note below), the sum of bases (SoB, compound metric for exchangeable Ca+Mg+K+Na), bioavailable P (resin), and cation exchange capacity (CEC). Soil exchangeable P (Mehlich-1) increased, but was not statistically significant.

Nutrient analysis note: Mehlich-1 is an extraction procedure to determine soil exchangeable P, K, and Na. It is suitable for acid and low cation exchange capacity soils typical for the tropics. Resin P captures phosphate anions through an exchange resin from the soil solution, aiming to measure the bioavailable P that plant roots can directly access (Sanchez, 2019). Soil exchangeable Ca and Mg are measured via a KCl 1 mol/L solution (Embrapa, 2017).

Table 2 summarizes the pairwise Δ soil health metrics for 0 and 20t/ha. Importantly, table 2 also shows the absolute soil health values after 9 months, all of which were higher for the basalt amended areas compared to the control (see Table 2).

The substantial increase in exchangeable Mehlich-1 phosphorus (+131.9%, p=0.09) and bioavailable resin phosphorus (+31.1%, p=0.013) is particularly noteworthy. Phosphorus is one of the most essential plant nutrients, yet P fertilizers are costly, often imported, and relatively inefficient in tropical soils because phosphorus is rapidly immobilized on soil particles and becomes unavailable to plants (Sanchez, 2019). The P content of our basalt (0.5% P2O5) is unlikely to explain this substantial increase alone, indicating that other indirect mechanisms, such as silicon (Si)-induced P mobilization, were involved (see e.g. Schaller et al., 2024). Accordingly, any amendment that mobilizes P already present in the soil and thereby reduces reliance on external fertilizer inputs offers a direct agronomic and economic benefit.

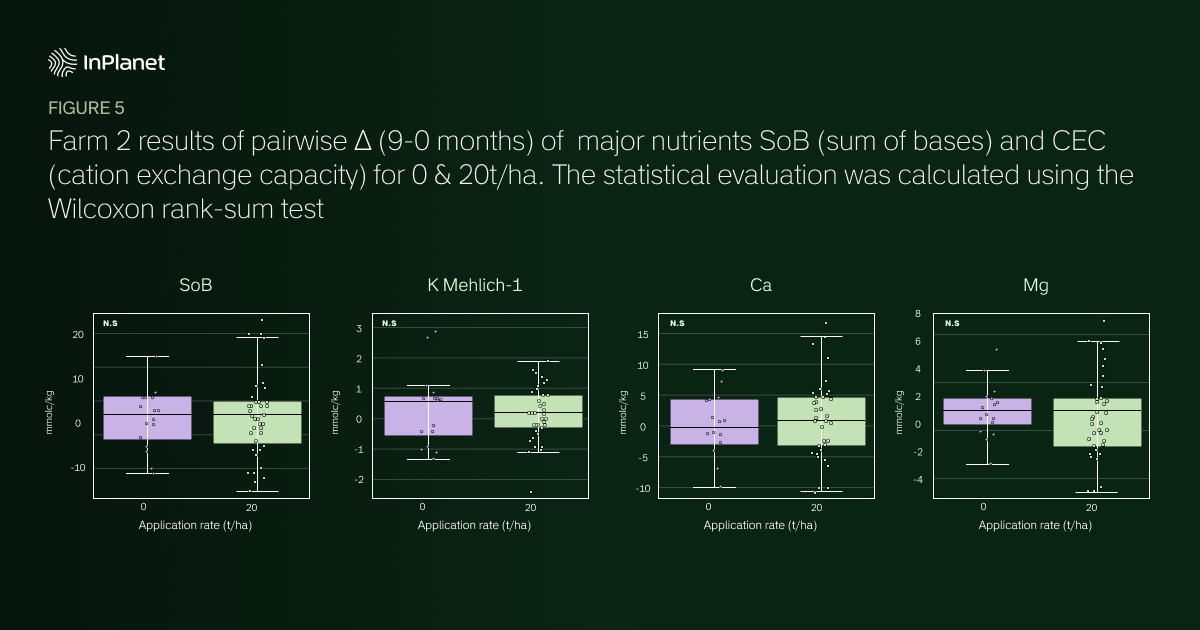

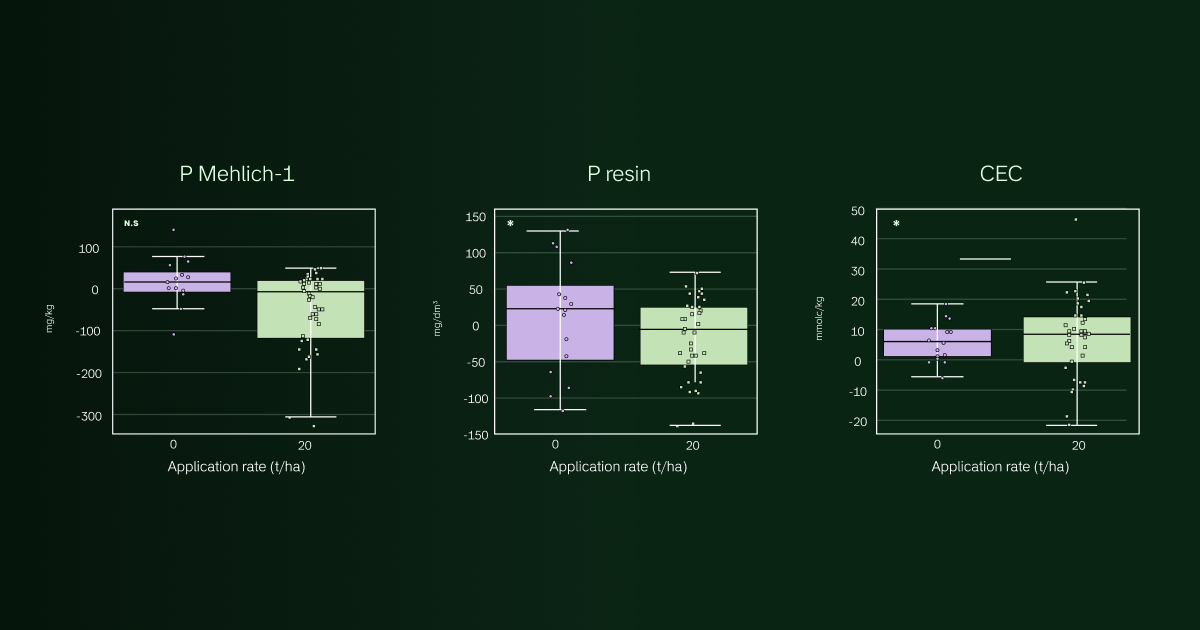

Farm 2 – Replacement of limestone and gypsum

In contrast to Farm 1, the basalt-treated areas of Farm 2 received no limestone or gypsum, so basalt fully replaced these amendments. The control areas received 2.8 t/ha limestone and 1.2 t/ha gypsum.

On farm 2, most Δ (9-0 months) soil health metrics (SoB, K, Ca, Mg, P-resin, and CEC) showed no statistically significant change between control and basalt (Figure 5). Ca had an increasing trend, whereas SoB, K, Mg, P-resin, and CEC showed a decreasing trend. Mehlich-1 P decreased significantly in the basalt-treated soils. Details about the pairwise Δ soil health metrics and the absolute values at 9 months can be found Table 3.

Importantly, one reason for the substantial difference in nutrient availability on farm 2 could be the replacement of limestone and gypsum, as both materials influence soil pH and nutrient dynamics. Furthermore, another reason could be that some of the basalt-treated areas received less conventional fertilizers than the control areas due to variable fertilization rates. This illustrates the real-world challenges of integrating our basalt applications into the dynamic operations of a commercial farm. It also underscores the value of controlled field experiments for reducing the heterogeneity introduced by operational and environmental variability.

Vegetation Analysis

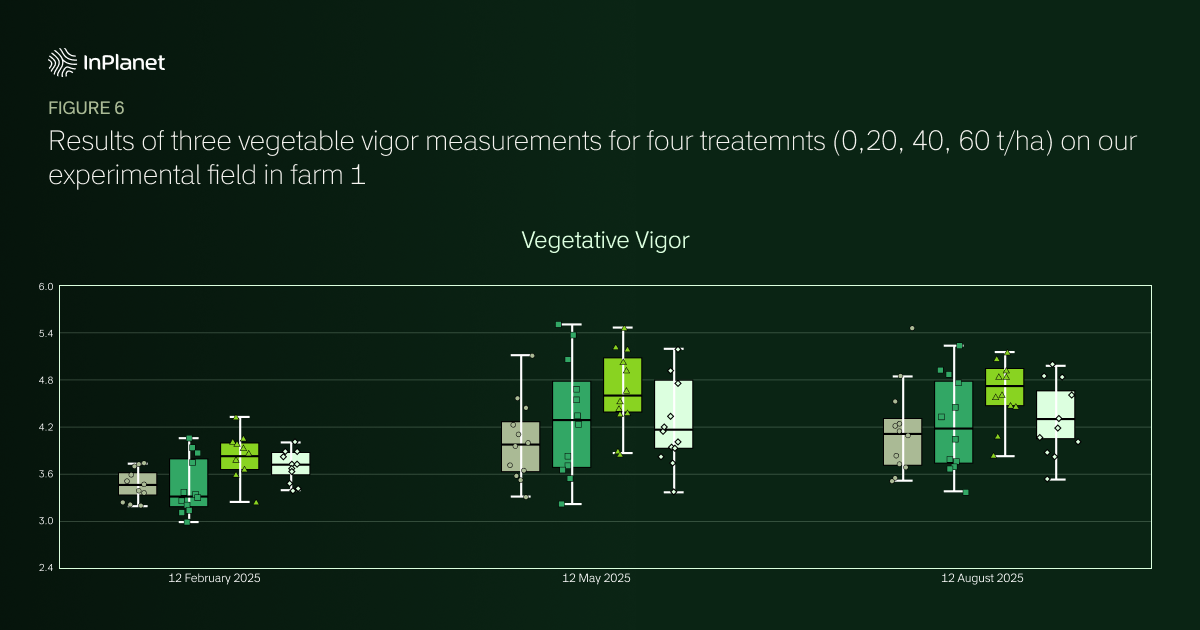

The biometric analysis was conducted on a controlled experimental site at farm 1 (BAU). Biometric measurements were performed every three months after application in an experimental block that also included higher basalt rates (40 and 60 t/ha).

Vegetative vigor (VV), a key indicator of overall plant health and growth potential, was quantified using a composite index (Bordignon et al., 2003). This index integrates the key growth parameters plant height (H), average canopy diameter (CD), and rootstock trunk diameter (RTD) into a single value. Across the range of application rates tested (0 to 60 t/ha), the vegetative vigor index remained stable, with no statistically significant differences (Wilcoxon rank-sum test) observed between the treatment groups (Figure 6). Although a moderate positive trend was noted particularly for 40 t/ha, citrus trees are not expected to respond as quickly to basalt application as fast-growing, nutrient-demanding crops such as soy or corn.

Ongoing fruit yield and nutrient analyses will provide the final agronomic picture and clarify how basalt influences nutrient uptake, fruit quality, and overall productivity.

Conclusion

Overall, the results from both farms show that basalt rock powder can improve soil health under typical citrus production conditions, with effects modulated by each farm´s baseline soil properties and management practices.

On Farm 1, that received limestone and fertilizers on the whole area, basalt application improved several soil health metrics, and tree vigor remained stable on the experimental site, with a tendency to increase for 40t/ha.

On Farm 2, basalt proved capable of replacing limestone as a pH corrective, though shifts in nutrient availability reflected the farm’s baseline conditions and fertilization strategy. These differences suggest that there is great potential for optimizing soil health using rock powder in combination with, or partially replacing, traditional amendment strategies. As yield and fruit quality data become available, we expect to quantify these benefits further.

Overall, these results highlight that basalt rock powder is a promising agronomic amendment for tropical citrus orchards, while simultaneously contributing to durable carbon dioxide removal through enhanced weathering.

We gratefully acknowledge the support and contributions of the many individuals that made this project a reality including the mining and farming partners, Mariane Chiapini, Marcella Daubermann, Veronica Furey, Junyao Kang, Niklas Kluger, Murilo Nascimento, Igor Nogueira, Bruno Ramos, Felipe Reis, Mayra Maniero Rodrigues, Leticia Schwerz, Jeandro Vitorio.

References

Bordignon, R., Medina Filho, H. P., Siqueira, W. J., & Pio, R. M. (2003). Características da laranjeira ‘Valência’ sobre clones e híbridos de porta-enxertos tolerantes à tristeza. Bragantia, 62, 381-395.

Costanzo, Sarah A., Iris O. Holzer, Nall I. Moonilall, Amber Davenport, Benjamin Z. Houlton, and Mallika A. Nocco. 2025. “Preliminary Assessment of Crushed Rock, Compost, and Biochar Amendments on Soil Physical Properties.” Agricultural & Environmental Letters 10 (2): e70028. https://doi.org/10.1002/ael2.70028.

Embrapa Solos. (2017). Manual de Métodos de Análise de Solo – Parte II: Análises Químicas. 3ª edição revista e ampliada. Rio de Janeiro: Embrapa.

Sanchez, Pedro (2019). Properties and Management of Soils in the Tropics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316809785.

Schaller, J., Webber, H., Ewert, F., Stein, M. & Puppe, D. (2024). The transformation of agriculture towards a silicon-improved sustainable and resilient crop production. npj Sustainable Agriculture, 2, Article 27. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-024-00035-z

Swoboda, Philipp, Thomas F. Döring, and Martin Hamer. 2022. “Remineralizing Soils? The Agricultural Usage of Silicate Rock Powders: A Review.” Science of The Total Environment 807 (February): 150976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150976

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service (USDA FAS). “Citrus: World Markets and Trade.” Published 30 January 2025. Available at: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/citrus-world-markets-and-trade-01302025

Authored by:

Dr. Christina Larkin

Head of Science & Research

Dr. Philipp Swoboda

Impact & Science Lead

Dr. Matthew Clarkson

Head of Carbon